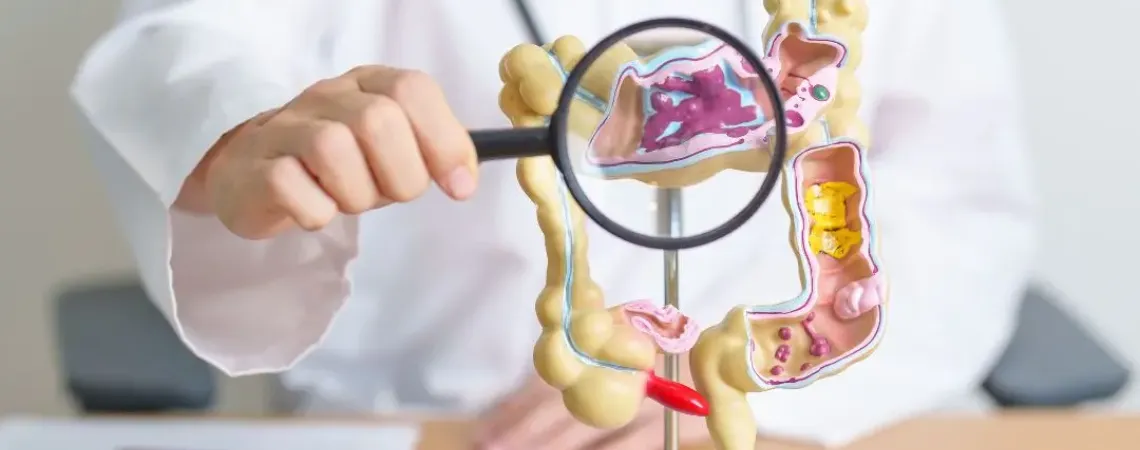

Diverticular disease particularly affects older populations: it is found in 20 to 50% of people over the age of 50, and in up to 66 to 85% of those aged 85 and older (1). Although often asymptomatic, it can progress to diverticulitis in 5 to 20% of cases, with a risk of serious complications sometimes requiring emergency surgery (2).

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Diverticular disease is characterized by the formation of diverticula—small pouches that develop in the wall of the colon (3). Diverticulosis is the silent form, which causes no symptoms or complications in the majority of cases (3). However, inflammation or infection of these diverticula, known as diverticulitis, can lead to abdominal pain, fever, and even severe complications such as abscesses, fistulas, intestinal obstructions, or perforations that may require surgical intervention (2).

Although the origin of this disease remains partially understood, several risk factors are well established: age, obesity, physical inactivity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and the use of certain medications (notably non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, and opioids) (4). Strong evidence also links dietary factors, such as red meat consumption (both processed and unprocessed), to increased risk. Limiting red meat intake to less than once per week is advised for primary prevention of diverticular disease (14), as risk increases linearly by about 50% when consumption exceeds 105–135 g per week, plateauing around 540 g per week (5). Additionally, a low-fibre diet may lead to chronic constipation and increased intraluminal pressure, which could contribute to diverticula formation (6). Other possible mechanisms involved in diverticula formation include connective tissue changes, abnormal intestinal motility, visceral hypersensitivity, gut microbiota dysbiosis, genetic predisposition, and collagen abnormalities in the intestinal wall (4).

Regarding the progression of the disease toward diverticulitis, epidemiological data suggest that chronic inflammation—indicated by blood markers such as CRP and IL-6, as well as the inflammatory potential of participants' dietary patterns—may be a key mechanism. These factors have been associated with an increased risk of incident diverticulitis in 59-year-old male patients (21). Indeed, those with the most pro-inflammatory diets had a 30% higher risk of developing diverticulitis over the following 8 years compared to those with the least inflammatory diets (21). A diet with anti-inflammatory potential—rich in leafy green vegetables, coffee, and tea, and low in red and processed meats, refined grains, and sugary beverages—could represent a promising nutritional strategy to reduce the risk of diverticulitis (21). However, to date, no clinical trials or international consensus allow for formal recommendations in this regard.

Therapies

Medical Treatments

For uncomplicated forms of diverticulitis, the latest guidelines suggest that routine use of antibiotics is not necessary in immunocompetent patients (7). In contrast, for patients with severe infection or abscess, antibiotic treatment combined with percutaneous drainage in the case of large abscesses is recommended (7). Anti-inflammatory treatments have shown some potential in reducing recurrences, though data remain controversial (7). In cases of major complications—such as perforation, massive bleeding, or intestinal obstruction—surgical intervention is necessary (7).

Nutritional Therapy

Symptomatic Phase: Low-Residue Diet and Probiotics

During episodes of acute diverticulitis, it is often recommended to temporarily adopt a clear liquid diet (water, clear broth, pulp-free juice) for a short period (2). Solid foods are then gradually reintroduced using a low-residue diet (low in indigestible components such as high-fibre foods, fruit and vegetable skins and seeds, tough meats, high-fat foods, etc.) (8). This transition helps reduce stool volume and frequency over a few days to weeks to alleviate symptoms (2). It is important to inform patients that this restrictive therapeutic diet is not suitable for long-term use, as it may cause deficiencies and worsen constipation. Once symptoms improve, a gradual reintroduction of dietary fibre and proper hydration, with the guidance of a registered dietitian, is recommended to prevent symptom flare-ups and reduce the risk of recurrence.

Regarding probiotics in diverticulitis treatment, while scientific evidence is still limited, some studies suggest that antibiotic treatment (ciprofloxacin/metronidazole) combined with Lactobacillus reuteri may offer additional benefits (reduction of pain, inflammatory markers, and hospital stay duration) compared to antibiotics with placebo (16). However, current guidelines do not support the routine use of probiotics due to limited and inconsistent evidence (14).

Asymptomatic Phase: Dietary Fibre and Food-Based Probiotics

Fibre—especially from fruits, vegetables, and whole grains—supports regular bowel movements, lowers colonic pressure, and helps reduce both local and systemic inflammation, making it a priority during the asymptomatic phase of diverticular disease (6, 9). Several studies have shown that high fibre intake (25–30 g per day or more) is associated with a significantly lower risk of developing diverticulitis or being hospitalized due to diverticular disease (6). However, the average daily fibre intake among Canadians is only 14 to 18 g (19). Observational data suggest that every additional 5 g of daily fibre may reduce the relative risk of diverticulitis by 30% (10). Ma et al. (2019) observed especially positive effects from fruit-based fibres, such as those found in apples, pears, and plums (11). These fruits are rich in soluble fibre, which helps soften stools and reduce constipation risk. Fibre supplementation, including psyllium (around 10 g per day), may relieve symptoms and reduce complications, though data on recurrence prevention remain inconclusive (12, 13).

Moreover, contrary to past beliefs, it is no longer recommended to systematically avoid nuts, seeds, corn, or foods containing small seeds like strawberries or tomatoes, out of fear they may become lodged in diverticula and trigger inflammation in people with diverticulosis. To date, no scientific evidence supports such dietary restrictions (14, 15).

Preliminary research suggests that certain probiotic strains from the Lactobacillus genus may be beneficial in maintaining remission in diverticular disease, but current data are insufficient to recommend specific supplements or dosages (17, 18). Nevertheless, a diet naturally rich in probiotics, including fermented foods like yogurt and kefir, may promote digestive health by improving microbial diversity, strengthening the intestinal barrier, and increasing anti-inflammatory metabolites (e.g., polyphenols, short-chain fatty acids) (20). However, no study to date has confirmed a direct protective effect against diverticula formation or progression to diverticulitis.

Nutrition plays a key role in both primary and secondary prevention of diverticular disease, helping to reduce the development of diverticula and the recurrence of diverticulitis. TeamNutrition’s dietitians offer valuable support in helping your patients adjust their diet—whether for prevention, symptom management during acute phases, or reducing the risk of recurrence after a flare-up. Help your patients find the dietitian that meets their needs.

References

- Fondation canadienne de la santé digestive. (2009). Faire de la santé digestive une priorité pour les Canadiens. La Fondation canadienne de la santé digestive – Rapport national sur la prévalence et l’impact des troubles digestifs.

- Fondation canadienne pour la santé digestive. (2025). La maladie diverticulaire. Retrieved from : https://cdhf.ca/fr/digestive-conditions/diverticular-disease/

- Baum, A., J., MD, Companioni, R. A. C., (2024). Diverticulose du côlon. Manual Merck. Retrieved from : https://www.merckmanuals.com/fr-ca/accueil/troubles-digestifs/maladie-diverticulaire/diverticulose-du-c%C3%B4lon

- Lanas, A., Abad-Baroja, D., & Lanas-Gimeno, A. (2018). Progress and challenges in the management of diverticular disease: which treatment?. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology, 11, 1756284818789055.

- Cao, Y., Strate, L. L., Keeley, B. R., Tam, I., Wu, K., Giovannucci, E. L., & Chan, A. T. (2018). Meat intake and risk of diverticulitis among men. Gut, 67(3), 466-472.

- Carabotti, M., Falangone, F., Cuomo, R., & Annibale, B. (2021). Role of dietary habits in the prevention of diverticular disease complications: a systematic review. Nutrients, 13(4), 1288.

- Sartelli, M., Weber, D. G., Kluger, Y., Ansaloni, L., Coccolini, F., Abu-Zidan, F., ... & Catena, F. (2020). 2020 update of the WSES guidelines for the management of acute colonic diverticulitis in the emergency setting. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 15, 1-18

- Kong, F., & Singh, R. P. (2008). Disintegration of solid foods in human stomach. Journal of food science, 73(5), R67-R80.

- Kuo, S. M. (2013). The interplay between fiber and the intestinal microbiome in the inflammatory response. Advances in Nutrition, 4(1), 16-28.

- Crowe, F. L., Balkwill, A., Cairns, B. J., Appleby, P. N., Green, J., Reeves, G. K., ... & Beral, V. (2014). Source of dietary fibre and diverticular disease incidence: a prospective study of UK women. Gut, 63(9), 1450-1456.

- Ma, W., Nguyen, L. H., Song, M., Jovani, M., Liu, P. H., Cao, Y., ... & Chan, A. T. (2019). Intake of dietary fiber, fruits, and vegetables and risk of diverticulitis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology| ACG, 114(9), 1531-1538.

- Maconi, G., Barbara, G., Bosetti, C., Cuomo, R., & Annibale, B. (2011). Treatment of diverticular disease of the colon and prevention of acute diverticulitis: a systematic review. Diseases of the colon & rectum, 54(10), 1326-1338.

- Ünlü, C., Daniels, L., Vrouenraets, B. C., & Boermeester, M. A. (2012). A systematic review of high-fibre dietary therapy in diverticular disease. International journal of colorectal disease, 27, 419-427.

- Kruis, W., Germer, C. T., Böhm, S., Dumoulin, F. L., Frieling, T., Hampe, J., ... & German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and the German Society of General and Visceral Surgery (DGAV)(AWMF‐Register 021‐20). (2022). German guideline diverticular disease/diverticulitis: Part II: Conservative, interventional and surgical management. United European Gastroenterology Journal, 10(9), 940-957.

- Strate, L. L., Liu, Y. L., Syngal, S., Aldoori, W. H., & Giovannucci, E. L. (2008). Nut, corn, and popcorn consumption and the incidence of diverticular disease. Jama, 300(8), 907-9

- Petruzziello, C., Migneco, A., Cardone, S., Covino, M., Saviano, A., Franceschi, F., & Ojetti, V. (2019). Supplementation with Lactobacillus reuteri ATCC PTA 4659 in patients affected by acute uncomplicated diverticulitis: A randomized double-blind placebo controlled trial. International journal of colorectal disease, 34, 1087-1094.

- Ojetti, V., Petruzziello, C., Cardone, S., Saviano, L., Migneco, A., Santarelli, L., ... & Franceschi, F. (2018). The use of probiotics in different phases of diverticular disease. Reviews on recent clinical trials, 13(2), 89-96

- Lahner, E., Bellisario, C., Hassan, C., Zullo, A., Esposito, G., & Annibale, B. (2016). Probiotics in the Treatment of Diverticular Disease. A Systematic Review. Journal of gastrointestinal and liver diseases : JGLD, 25(1), 79–86.

- Ahmed, M., Praneet Ng, A., & L'Abbe, M. R. (2021). Nutrient intakes of Canadian adults: results from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS)-2015 Public Use Microdata File. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 114(3), 1131–1140

- Leeuwendaal, N. K., Stanton, C., O'Toole, P. W., & Beresford, T. P. (2022). Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients, 14(7), 1527. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14071527

- Ma, W., Jovani, M., Nguyen, L. H., Tabung, F. K., Song, M., Liu, P. H., ... & Chan, A. T. (2020). Association between inflammatory diets, circulating markers of inflammation, and risk of diverticulitis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 18(10), 2279-2286.