The “intuitive eating (IE)” approach is gaining in popularity and becoming increasingly discussed on social media. Presented as an alternative to dieting, it is sometimes interpreted as a movement denying the importance of food quality and weight. But is this really the case?

What is IE, and where does this approach come from?

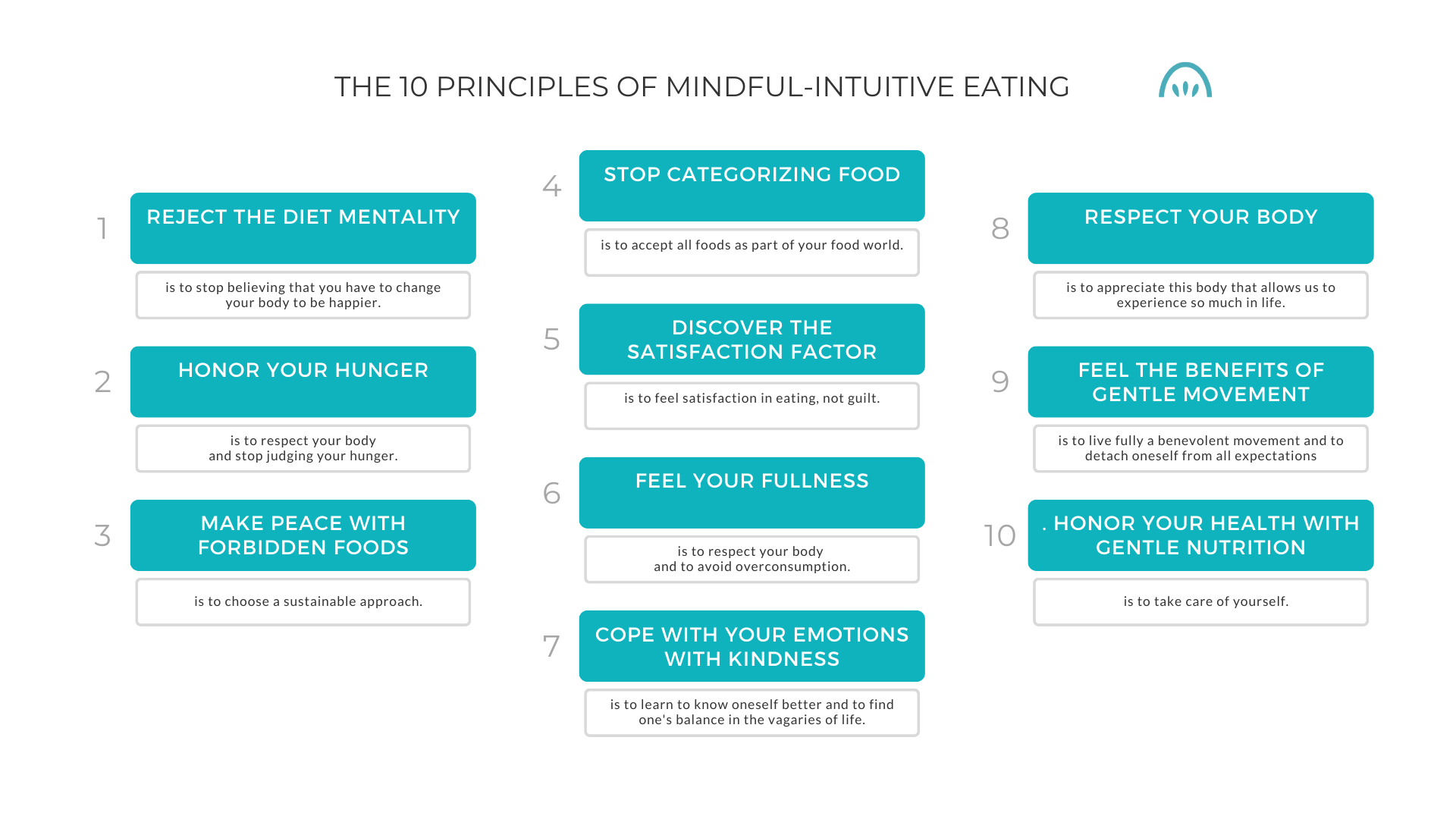

IE was developed by two nutritionists, Evelyne Tribole and Elyse Resh, in 1995 (1). They observed that prescribed diets did not allow their clients to maintain long-term weight loss, which led them to developing an alternative (1). IE was popularized by nutritionist Karine Gravel via her thesis, published in 2013 (2). IE allows patients to recognize the physiological signals related to hunger and satiety, to consider the emotion associated with food intake, to recognize without judgment the reasons that push us to eat without hunger or push us to exceed our satiety and allows long-term weight regulation (3-5). IE can be divided into ten main principles:

IE’s patient-centered approach promotes body diversity, focuses on the impacts on health and quality of life and not only on weight, allows for a reconnection to our hunger and satiety cues, allows for a reduction in guilt and the notion that certain foods are to be banned, and allows for the integration of healthy eating and increased physical activity for the sake of it (5-7).

How does EI impact weight loss?

Although the goal of IE is not weight loss, some studies have looked specifically at its results in this context. According to a meta-analysis published in 2019, significantly more weight loss in participants undergoing an IE-based intervention was observed compared to a non-diet control group. The weight loss was not significantly different from the diet control group, suggesting that IE may result in similar weight loss as a traditional diet (8). In another meta-analysis published the following year, greater weight loss was observed in participants with a weight loss intervention, but this difference was not significant (9). Another meta-analysis reports moderate weight loss with a mindfulness-based intervention (10). A similar meta-analysis reported a 4.2 kg loss in overweight or obese participants (11).

Although IE is not intended for weight loss, these studies suggest that it may assist with this health parameter. This is also reported in the new 2020 obesity management guidelines (7).

Does IE impact food quality?

Some health professionals question the impact of IE on dietary quality. According to a systematic review published in 2021, most studies report no difference in dietary intake between participants receiving IE interventions compared to control groups (12). However, interpretation of the results must be done with caution, as the studies contained a limited number of participants, were done over a short time, and the groups were generally homogeneous (usually overweight women). A cross-sectional study of 1860 participants also reported greater fruit and vegetable consumption in students who naturally had a more intuitive diet, according to a questionnaire (13). This association is not as clear with other food groups. One large study observes discordant effects of IE on food quality. Some IE components (such as respecting one's hunger and satiety cues and eating for physiological rather than emotional reasons) were associated with greater vegetable and whole grain consumption in women, but this relationship was not observed in men (14). Conversely, lower consumption of soft drinks and salty snacks was observed with these components for both sexes (14). Similar results were reported in the NutriNet-Santé study (15).

Although the relationship between IE and dietary quality still needs to be understood, studies show that some concepts of mindful eating, such as respect for hunger and satiety cues, may be associated with better dietary quality.

What are the psychological impacts of IE?

According to the new guidelines for obesity management, IE (as well as other anti-dieting approaches) may be effective for binge-eating and other disorders and positively influence eating behaviors (7).

Indeed, according to a review of the literature, people who eat more intuitively are less likely to suffer from eating disorders and to diet (16). However, the literature is more limited regarding other eating behaviors (16). Studies report that IE is associated with positive body image and other psychological aspects, such as higher self-esteem, better listening and sensitivity to bodily cues (including listening for hunger and satiety signals), and greater motivation to engage in physical activity (16). A recent meta-analysis reports that IE is inversely associated with several indices of pathological eating, body image disturbance, and psychological distress, and is positively associated with several positive psychological constructs (17). However, these studies are generally cross-sectional, limiting the possibility of establishing cause. Also, an 8-year longitudinal study of adolescents found that an increase in IE over time was associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms, low self-esteem, body dissatisfaction, binge eating, and harmful or extreme weight control behaviors (18).

Although more studies are needed, IE appears to be positively related to several elements of psychological well-being and a decreased risk of developing eating disorders.

What does this mean?

IE is an interesting avenue for your clients suffering from a conflictual relationship with food or an eating disorder such as binge eating, and it could help stabilize (and perhaps reduce) the weight of clients who have dieted repeatedly. A TeamNutrition nutritionist can help discover the best approach for your client based on their eating habits, weight history, and relationship with food. Please contact us for more information on our professional services.

References

Tribole, E., & Resch, E. (1995). Intuitive Eating : A Revolutionary Program That Works. Saint Martin’s Paperbacks, New York.

Gravel, K. (2013). Manger avec sa tête ou selon ses sens : perceptions et comportements alimentaires, thèse de Doctorat, Université Laval Québec, Canada.

Dugmore, JA., Winten, CG., Niven, HE., Bauer, J. (2020). Effects of weight-neutral approaches compared with traditional weight-loss approaches on behavioral, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev.; 78(1):39-55. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuz020.

Ulian, MD., Aburad, L., da Silva Oliveira, MS., et al. (2018). Effects of health at every size interventions on health-related outcomes of people with overweight and obesity: a systematic review. Obes Rev.;19(12):1659-1666. doi:10.1111/ obr.12749.

Warren, JM., Smith, N., and Ashwell, M. (2017). A structured review on the role of mindfulness, mindful eating and intuitive eating in changing eating behaviours: effectiveness and associated potential mechanisms. Nutr Res Rev; 30(2):272-283.

Robison, J. (2005) Health at Every Size: Toward a new Paradigm of weight and health, Med Gen Med.; 7(3).

Brown, J., Clarke, C., Johnson Stoklossa, C., et al. Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines: Medical Nutrition Therapy in Obesity Management. Available from: https://obesitycanada.ca/guidelines/nutrition. Consulté le 18 avril 2022.

Artiles, RF., Staub, K., Aldakak, A., et al. (2019).Mindful eating and common diet programs lower body weight similarly: Systematic review and meta-analysis.Obes Rev; 20(11):1619-1627.

Dugmore, SA., Winten, CG., Niven, HE. et Bauer J. (2020). Effects of weight-neutral approaches compared with traditional weight-loss approaches on behavioral, physical, and psychological health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutr Rev;78(1):39-55.

Carrière, K., Khoury, B., Günak, MM. et Knäuper, B. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obes Rev;19(2):164-177. doi:10.1111/obr.12623.

Rogers, JM., Ferrari, M., Mosely, K., et al. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions for adults who are overweight or obese: a meta-analysis of physical and psychological health outcomes. Obes Rev;18(1):51-67.

Grinder, HS., Douglas, SM. et Raynor HA. The Influence of Mindful Eating and/or Intuitive Eating Approaches on Dietary Intake: A Systematic Review. (2021). J Acad Nutr Diet;121(4):709-727.

Christoph, MJ. Hazzard, VM., Järvelä-Reijonen, E. et al. Intuitive Eating is Associated With Higher Fruit and Vegetable Intake Among Adults. (2021). J Nutr Educ Behav;53(3):240-245.

Horwath, C., Hagmann, D ,et Hartmann, C. (2019). Intuitive eating and food intake in men and women: results from the Swiss food panel study. Appetite;135:61-71.

Camilleri, GM., Méjean, C., Bellisle, F. et al. (2017). Intuitive eating dimensions were differently associated with food intake in the general population-based NutriNet-Santé study. J Nutr;147: 61–69.

Bruce, LJ. et Ricciardelli LA. A systematic review of the psychosocial correlates of intuitive eating among adult women. (2016). Appetite; 96:454-472.

Linardon, J,. Tylka, TL. et Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. Intuitive eating and its psychological correlates: A meta-analysis. (2021). Int J Eat Disord;54(7):1073-1098.

Hazzard, VM., Telke, SE., Simone, M. et al. Intuitive Eating Longitudinally Predicts Better Psychological Health and Lower Use of Disordered Eating Behaviors: Findings from EAT 2010–2018. (2021). Eat Weight Disord;26(1):287-294.