Published on March 29, 2024

Pathophysiology of Gout

Gout is a form of inflammatory arthritis that is often misunderstood despite its prevalence and impact on the quality of life of individuals living with this condition. Each year, approximately 681,000 adults in Canada are diagnosed with gout (1). It is characterized by pain and swelling in the joints, mainly localized in the big toe, but can also affect other joints such as the knees, ankles, hands, and elbows (2).

Etiology, Symptoms, and Risk Factors

Gout occurs when the body produces an excess of uric acid or has difficulty eliminating it effectively. Uric acid is generated by the breakdown of certain molecules such as purines (3). Normally, the kidneys filter uric acid from the blood and then eliminate it through urine. However, in some cases, the body produces too much uric acid or the kidneys do not eliminate it quickly enough, leading to hyperuricemia. Uric acid crystals can then accumulate in the joints, causing the symptoms of gout (2). Overweight, obesity, congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension, kidney disease, as well as excessive alcohol intake and animal protein consumption are all established risk factors that increase the likelihood of experiencing gout attacks. However, genetic predispositions play a crucial role in the development and severity of hyperuricemia and gout, as revealed by a 2018 meta-analysis (4). While health professionals should educate their patients-clients about adopting dietary habits to reduce their risks of recurrence and symptoms, it is important to recognize the genetic impact on the development of this disease to avoid stigmatization.

Nutritional Therapy

Low-Purine Diet

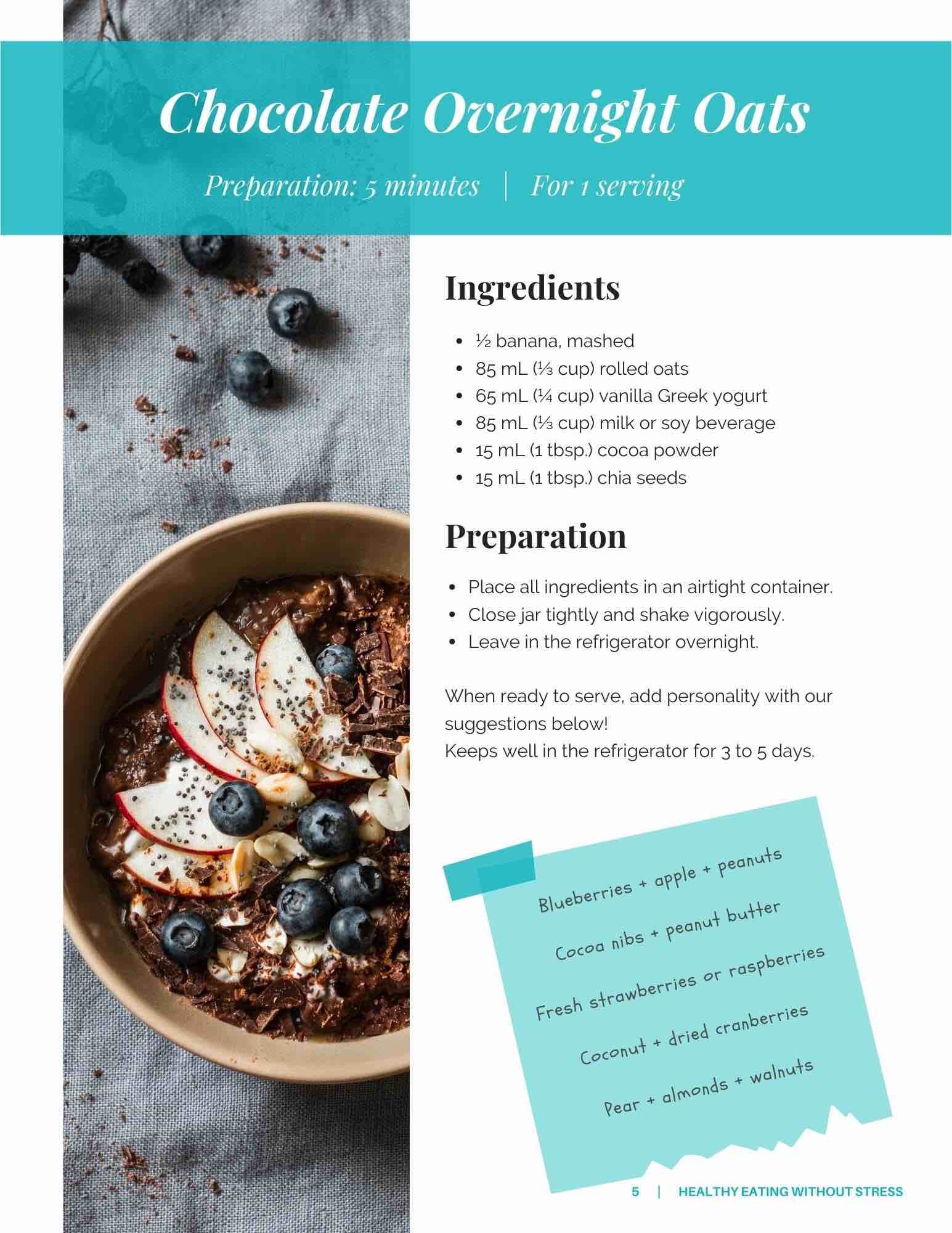

The low-purine diet is a recommended nutritional approach for managing gout symptoms, as stated in the guidelines published in 2020 by the American College of Rheumatology (5). Foods rich in purines include meat, poultry, fish, and seafood. Dairy products, such as milk, yogurt, and cheese, as well as eggs are low-purine foods, and should be preferred as a source of animal protein in a low-purine diet. There is no evidence demonstrating an association between gout and dairy products. However, there are currently no specific recommendations for adjusting dairy intake as the evidence comes mainly from low-quality observational studies (5, 6). In addition, certain plant-based foods are rich in purines, such as cauliflower and spinach. However, these foods appear to have an inverse association with uric acid levels in the body and the onset of gout symptoms, likely owing to the much lower bioavailability of the purines present in vegetables compared to those in animal products (7). For this reason, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, and soy-based products should also be prioritized in a low-purine diet.

Alcohol and Fructose

Alcohol can also contribute to an increase in blood uric acid levels by decreasing its excretion and promoting its production, particularly by accelerating the degradation of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies by Li et al. (2018) highlighted an association between high alcohol consumption and an increased risk of hyperuricemia and gout attacks compared to no alcohol consumption (8). Additionally, a dose-response relationship between alcohol consumption and the incidence of gout attacks was observed (8, 9).

Excessive fructose intake can also increase uric acid levels by causing an acute overload in the liver. This promotes hyperuricemia by increasing adenosine monophosphate (AMP) levels, which are then degraded into uric acid (7). A 2023 umbrella review combining multiple meta-analyses and systematic reviews confirmed a positive association between sugar consumption, especially sugary drinks, and an increased risk of developing gout, although the quality of evidence varies (10). However, these results do not apply to fructose present in much smaller amounts in whole fruits (excluding fruit juice). A study conducted in the United States on 28,990 participants showed that those who consumed an average of more than two servings of fruit per day had a 50% reduced risk of gout compared to those consuming less than half a serving per day (11).

Foods with Little or No Evidence

Contrary to popular beliefs, adding vitamin C supplements is not recommended for patients with gout (5, 6). Two randomized controlled trials showed no clinically significant effect on serum urate levels after vitamin C supplementation (12, 13). Regarding cherries, cherry extracts, and cherry juice, some hypotheses suggest that the anti-inflammatory properties of anthocyanins in this fruit could reduce gout attacks. However, the results of clinical trials are variable. For example, one study observed a significant reduction in gout attacks in overweight or obese adults who consumed cherry juice, while another study found no effect of cherry juice concentrate on blood uric acid concentration or short-term gout attacks (14, 15). Currently, gout treatment guidelines provide no recommendation regarding cherries.

And What About the Risks?

A low-purine diet may pose risks, including limiting sources of essential nutrients such as omega-3s and reducing the diversity of protein sources due to numerous restrictions. While the diet may help reduce uric acid levels and symptom development, it is rarely sufficient as a sole treatment. Nutritional therapy should be combined with other therapeutic treatments to ensure comprehensive and effective management of this inflammatory condition.

Given that this diet poses some long-term risks, a multidisciplinary approach including a nutritionist from TeamNutrition is crucial to support your patients-clients in making dietary changes while preventing nutritional deficiencies. Our KoalaPro platform offers a multitude of recipes rich in plant-based proteins, ideal for a low-purine diet, along with recipes for delicious mocktails to assist in reducing alcohol consumption. Contact us to explore our services and learn more.

References

- Government of Canada. (2020). Goutte et arthropathies cristallines. Santé Canada. Retrieved from https://www.canada.ca/fr/sante-publique/services/publications/maladies-et-affections/goutte-arthropathies-cristallines.html

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). Gout. Retrieved from https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/4755-gout

- Gaffo, A. J. (2023). Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of gout. UpToDate. Retrieved from www.uptodate.com

- Major, T. J., Topless, R. K., Dalbeth, N., & Merriman, T. R. (2018). Evaluation of the diet wide contribution to serum urate levels: meta-analysis of population based cohorts. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 363, k3951.

- FitzGerald, J. D., Dalbeth, N., Mikuls, T., Brignardello-Petersen, R., Guyatt, G., Abeles, A. M., Gelber, A. C., Harrold, L. R., Khanna, D., King, C., Levy, G., Libbey, C., Mount, D., Pillinger, M. H., Rosenthal, A., Singh, J. A., Sims, J. E., Smith, B. J., Wenger, N. S., Bae, S. S., … Neogi, T. (2020). 2020 American College of Rheumatology Guideline for the Management of Gout. Arthritis care & research, 72(6), 744–760.

- Neilson, J., Bonnon, A., Dickson, A., Roddy, E., & Guideline Committee (2022). Gout: diagnosis and management-summary of NICE guidance. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 378, o1754.

- Dietitians of Canada. (2023). Gout Knowledge Pathway. PEN. Retrieved from https://www.pennutrition.com/index.aspx

- Li, R., Yu, K., & Li, C. (2018). Dietary factors and risk of gout and hyperuricemia: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Asia Pacific journal of clinical nutrition, 27(6),

- Neogi, T., Chen, C., Niu, J., Chaisson, C., Hunter, D. J., & Zhang, Y. (2014). Alcohol quantity and type on risk of recurrent gout attacks: an internet-based case-crossover study. The American journal of medicine, 127(4), 311–318.

- Huang, Y., Chen, Z., Chen, B., Li, J., Yuan, X., Li, J., Wang, W., Dai, T., Chen, H., Wang, Y., Wang, R., Wang, P., Guo, J., Dong, Q., Liu, C., Wei, Q., Cao, D., & Liu, L. (2023). Dietary sugar consumption and health: umbrella review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.), 381, e071609.

- Williams P. T. (2008). Effects of diet, physical activity and performance, and body weight on incident gout in ostensibly healthy, vigorously active men. The American journal of clinical nutrition, 87(5), 1480–1487.

- Holland, R., & McGill, N. W. (2015). Comprehensive dietary education in treated gout patients does not further improve serum urate. Internal medicine journal, 45(2), 189–194.

- Stamp, L. K., O'Donnell, J. L., Frampton, C., Drake, J. M., Zhang, M., & Chapman, P. T. (2013). Clinically insignificant effect of supplemental vitamin C on serum urate in patients with gout: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Arthritis and rheumatism, 65(6), 1636–1642.

- Martin, K. R., & Coles, K. M. (2019). Consumption of 100% tart cherry juice reduces serum urate in overweight and obese adults. Current Developments in Nutrition, 3(5), nzz011.

- Stamp, L. K., Chapman, P., Frampton, C., Duffull, S. B., Drake, J., Zhang, Y., & Neogi, T. (2020). Lack of effect of tart cherry concentrate dose on serum urate in people with gout. Rheumatology (Oxford, England), 59(9), 2374–2380.